When Indiana adopted new U.S. House districts four years ago, Republican legislative leaders lauded them as 'fair maps' that reflected the state's communities.

But when Gov. Mike Braun recently tried to redraw the lines to help Republicans gain more power, he implored lawmakers to 'vote for fair maps.'

What changed? The definition of 'fair.'

As states undertake mid-decade redistricting instigated by President Donald Trump, Republicans and Democrats are using a tit-for-tat definition of fairness to justify districts that split communities in an attempt to send politically lopsided delegations to Congress. It is fair, they argue, because other states have done the same. And it is necessary, they claim, to maintain a partisan balance in the House of Representatives that resembles the national political divide.

This new vision for drawing congressional maps is creating a winner-take-all scenario that treats the House, traditionally a more diverse patchwork of politicians, like the Senate, where members reflect a state's majority party. The result could be reduced power for minority communities, less attention to certain issues, and fewer distinct voices heard in Washington.

Although Indiana state senators rejected a new map backed by Trump and Braun that could have helped Republicans win all nine of the state's congressional seats, districts have already been redrawn in Texas, California, Missouri, North Carolina, and Ohio. Other states could consider changes before the 2026 midterms that will determine control of Congress.

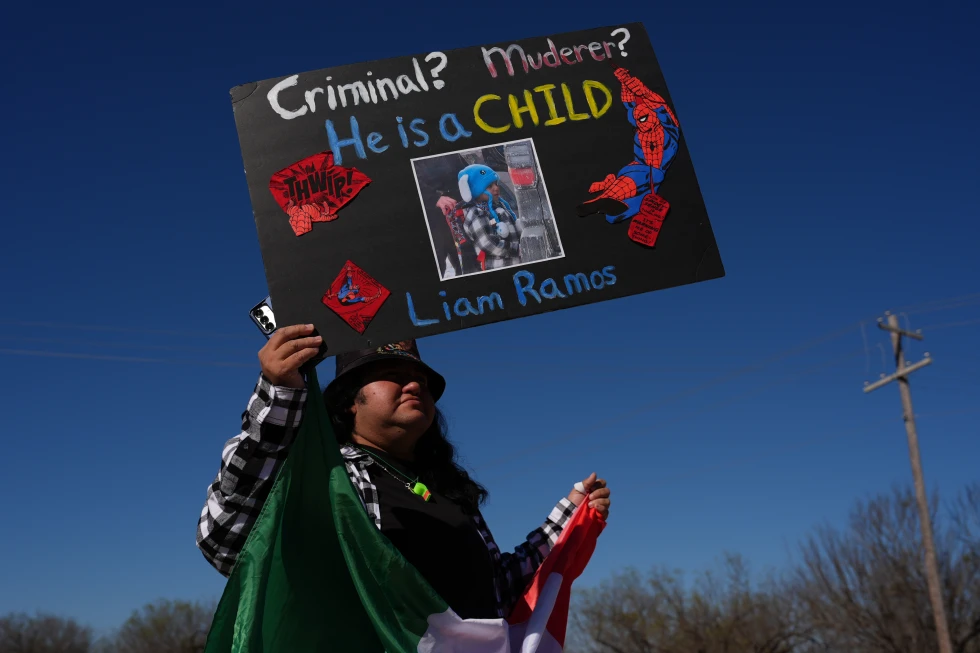

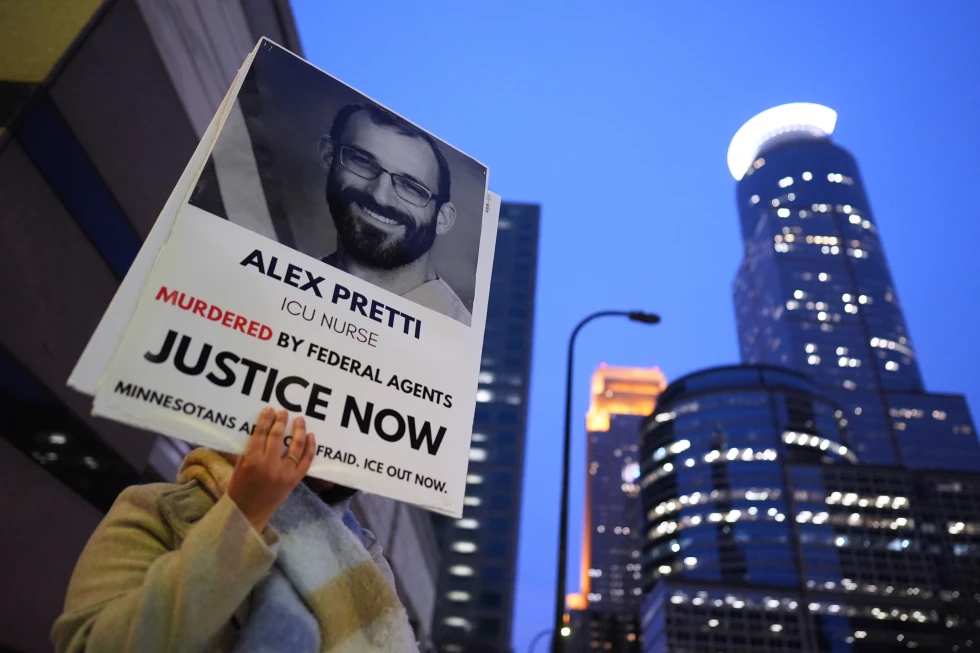

Redistricting is diluting community representation

Under the Constitution, the Senate has two members from each state. The House has 435 seats divided among states based on population, with each state guaranteed at least one representative. In the current Congress, California has the most at 52, followed by Texas with 38.

Because senators are elected statewide, they are almost always political pairs of one party or another. Pennsylvania and Wisconsin are the only states now with both a Democrat and Republican in the Senate.

By contrast, most states elect a mixture of Democrats and Republicans to the House. That is because House districts, with an average of 761,000 residents, based on the 2020 census, are more likely to reflect the varying partisan preferences of urban or rural voters, as well as different racial, ethnic, and economic groups.

This year's redistricting is diminishing those locally unique districts.

In California, voters in several rural counties that backed Trump were separated from similar rural areas and attached to a reshaped congressional district containing liberal coastal communities. In Missouri, Democratic-leaning voters in Kansas City were split from one main congressional district into three, with each revised district stretching deep into rural Republican areas.

Some residents complained their voices are getting drowned out. But Governors Gavin Newsom, D-Calif., and Mike Kehoe, R-Mo., defended the gerrymandering as a means of countering other states and amplifying the voices of those aligned with the state's majority.

Disrupting an equilibrium

By some national measurements, the U.S. House already is politically fair. The 220-215 majority that Republicans won over Democrats in the 2024 elections almost perfectly aligns with the share of the vote the two parties received. However, the partisan divisions have contributed to a 'cutthroat political environment' that drives the parties to extreme measures.

Rebekah Caruthers, who leads the Fair Elections Center, emphasizes that compact districts should allow communities of interest to elect their representatives, arguing that gerrymandering results in unfair disenfranchisement for some voters. Ultimately, she asserts, this gerrymandering is not good for democracy and calls for a need for some type of détente.