Syria will hold its first parliamentary elections on Sunday since the fall of Bashar al-Assad, amid concerns over inclusivity and successive delays.

There will be no direct vote for the People's Assembly, which will be responsible for legislation during a transitional period. Instead, electoral colleges will select representatives for two-thirds of the 210 seats, while interim President Ahmed al-Sharaa will appoint the remaining members.

Long-time former President Assad was ousted by Sharaa's forces 10 months ago following over a decade of civil strife. However, authorities have postponed elections in two Kurdish-controlled provinces and a third area due to recent violent clashes.

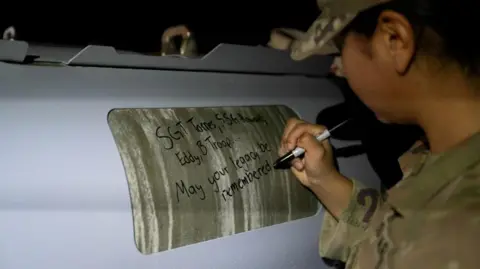

The clashes in July signify ongoing sectarian violence in Syria from Assad's era. In his speech at the UN General Assembly last week, Sharaa assured the pursuit of justice for those responsible for the conflict's atrocities, promising a commitment to rebuilding and establishing a new state with equitable laws.

Sunday's polls are being overseen by the Higher Committee for the Syrian People's Assembly Elections, yet the decision to suppress voting in Raqqa, Hassakeh, and Suweida means electoral colleges in only 50 out of 60 districts will choose representatives for around 120 seats.

With over 1,500 candidates ready for the elections, significant restrictions remain, including the exclusion of those affiliated with the Assad regime or foreign intervention advocates from running. While the electoral college mandates at least 20% female representation, there are no quotas for female lawmakers or representatives from diverse ethnic and religious communities, raising alarms about true representation.

Critics like Thouraya Mustafa from the Kurdish Democratic Union Party (PYD) argue that the elections reflect an authoritarian approach, undermining the foundational aim of democracy in representing the Syrian populace.

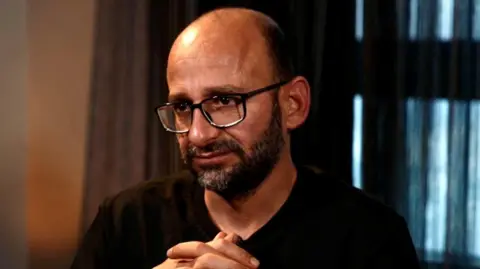

Sharaa defends the electoral process, noting the challenges due to the refugee population and loss of civil documentation, but many citizens, including Hussam Nasreddin, voice doubts, questioning the legitimacy and transparency of the assembly's composition.