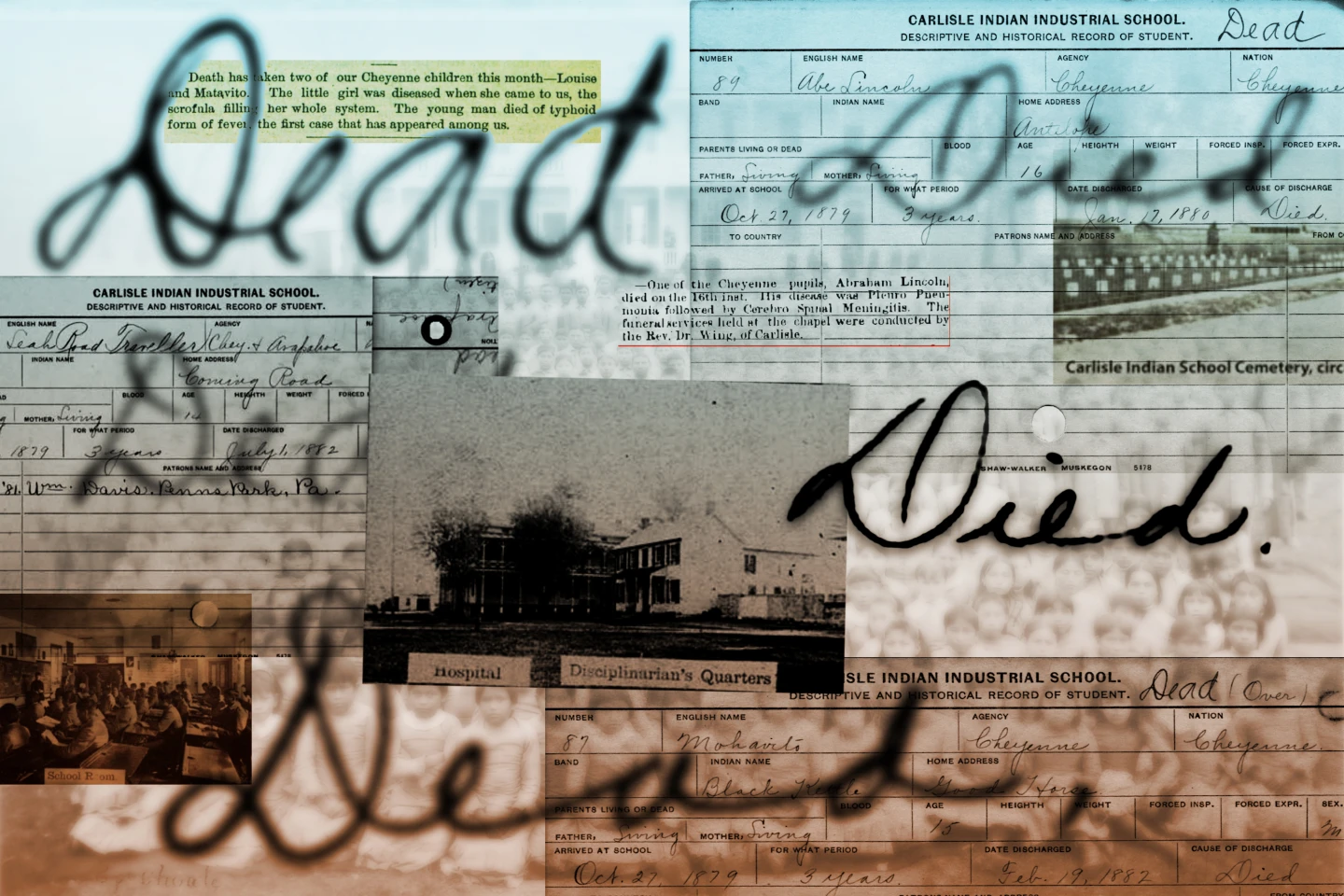

The Carlisle Indian Industrial School had not yet held its first class when Matavito Horse and Leah Road Traveler were taken there in October 1879, drafted into the U.S. government’s campaign to erase Native American tribes by wiping their children’s identities. A few years later, Matavito, a Cheyenne boy, and Leah, an Arapaho girl, were dead.

Persistent efforts by their tribes have finally brought them home. The Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes of Oklahoma recently received the remains of 16 children, exhumed from a Pennsylvania cemetery, and reburied their small wooden coffins last month in a tribal cemetery in Concho, Oklahoma. A 17th student, Wallace Perryman, was repatriated to the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma in Wewoka.

Burial ceremonies are considered “an important step toward justice and healing for the families and Tribal Nations impacted by the boarding school era,” according to the Cheyenne and Arapaho government. Officials also noted the need to address the trauma and lack of records surrounding the children’s identities and experiences at the boarding school.

Many details of the students’ lives remain elusive, but records shed light on their experiences where over 7,800 students from more than 100 tribes were sent amid genocidal warfare as the U.S. government seized land for white settlers.

For many families, the repatriation and burial of their children mark both a return and a reigniting of painful memories associated with forced assimilation practices. The significance of this act reverberates through the communities impacted, allowing for a moment of reflection and grief among those seeking closure.

However, not all tribes wish to disturb the burials of their children, and identification remains a significant challenge. Historical inaccuracies in records have complicated the repatriation process, necessitating further examination and collaboration with forensic experts to oversee these sensitive matters.

As more remains are exhumed from boarding school cemeteries, it is crucial for government bodies and agencies to acknowledge and assist the tribes in their healing journeys. This includes providing necessary funding and resources to continue the work of repatriation, thus honoring the legacy of those who were lost. The ongoing journey towards healing reflects the broader movement for recognition and respect for Native American rights and histories.