Many of the parents whose children were abducted 10 days ago from a boarding school in Nigeria are terrified - they do not want to talk to the authorities or journalists in case of reprisals from the kidnappers.

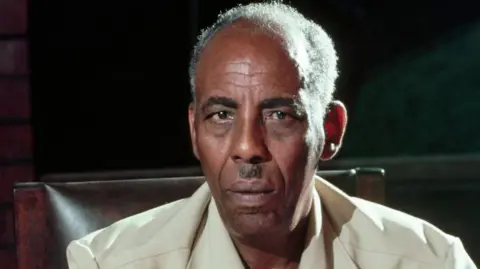

If they hear you say anything about them, before you know it they'll come for you. They'll come to your house and take you into the bush, one of them told the BBC. For his safety the BBC is not identifying him and is calling him Aliyu.

His young son is one of more 300 students abducted when armed men stormed the grounds of St Mary's Catholic School in Papiri village in the central state of Niger in the early hours of 21 November.

Some of the children taken are as young as five years old. About 250 are still reportedly missing, though state officials have said this number is exaggerated.

The incident is part of a recent wave of mass abductions in north and central Nigeria - some of which have been blamed on criminal gangs, known locally as bandits, who see kidnapping for ransom as a quick and easy way to make money.

Our village is remote, we are close to the bandits, explained Aliyu, whose son is still among the missing.

It's a three-hour drive to where they hide. We know where they are, but we can't go there ourselves, it's too dangerous.

He is desperate with worry - especially as vulnerable captives kept in forest hideouts have died during previous abductions, whether from sickness or because ransoms have not been paid.

I feel so bitter and my wife hasn't eaten for days… We're not happy at all. We need someone to help us to take action.

A few days before the Papiri kidnapping, 25 girls were taken from their school in Maga, which is 200km (125 miles) further north in Kebbi state.

One of the students escaped before the rest were rescued by the security forces last week from what the authorities said was a farm settlement.

Bandits tend to live in cattle camps deep in the bush. The gangs are largely composed of ethnic Fulani people, who are traditionally nomadic herders.

No details have been released about whether a ransom was paid to free the girls from Maga.

In fact, it is illegal to pay ransoms in Nigeria. However, if they are not paid hostages can be - and have been - killed.

Relatives tend to crowdfund or in the case of mass school abductions, the authorities are sometimes suspected of negotiating for their release.

No group has said it was behind these two recent school kidnappings, though the government has recently told the BBC it believes it was jihadists, not bandits, who are responsible. Locals in Kebbi and Niger states are likely to be curious for more information on this.

Yusuf, the legal guardian to some of the Maga girls and whose name has also been changed to protect his identity, believes such kidnappings could not have happened without informants in the community.

All these abductions are not common in Kebbi. These kidnappings can only happen with the connivance of someone from the community, because no stranger can come to a place and pull something like this off without the help of locals, he told the BBC.

There has been a surprising change of approach in some areas where villages have been at the mercy of bandits for the last decade and have given up hope of getting help from the security forces.

It has led some of these rural communities, who live in close proximity to the kidnapping gangs and in the woeful absence of effective policing, to come up with their own solutions.

In the north-west, those communities that have been severely affected by these mass kidnappings have struck so-called peace deals with these bandits in exchange for access to mines, David Nwaugwe, a security analyst for security risk consulting firm SBM Intelligence, told the BBC.

Many states in the north-west are rich in untapped mineral deposits - especially gold, a profitable prospect for bandit gangs.

These deals, according to Mr Nwaugwe, have been effective in some areas. What we've seen over time is that there seems to be some sort of a decline in the rate of attacks, he said.

Katsina state, in Nigeria's far north, is a case in point. It has long been synonymous with insecurity - particularly banditry and mass kidnappings. But in the past year, things have begun to shift, thanks in part to several peace deals struck between bandit leaders and community leaders.

Sitting on mats under the shade of wide trees, representatives from both sides hash out their terms and conditions before eventually coming to an agreement.

High on the agenda - for both sides - was the release of those kidnapped. The BBC does not know how many people were released in Jibia, but 37 villagers had been freed in Kurfi, another area of Katsina state, by late September - a month after a deal was struck.

Some have questioned whether the resurgence in attacks in the last few weeks is linked to Donald Trump's recent threats of military intervention in Nigeria.

The government and security analysts have been at pains to point out that both Muslims and Christians have been targets in mass kidnappings. Nigeria's security situation is now very complicated. We don't know how to draw the lines between violent extremist groups or bandits. Because they operate almost in the same areas and in a fluid manner.

As far as he is concerned, stopping the violence will require a two-pronged approach - a combination of armed confrontation and negotiating amnesty deals.

But for the parents of Papiri, the prospect of living peacefully with the enemy remains a far-off dream as they pray for their children's safe return.