For millions across northern India, the November air tastes ashy, the sky looks visibly hazy, and merely stepping outside feels like a challenge.

For many, their morning routine starts with checking how bad the air is. But what they see depends entirely on which monitor they use.

Government-backed apps like SAFAR and SAMEER top out at 500 - the upper limit of India's AQI (air quality index) scale, which converts complex data on various pollutants such as PM2.5, PM10, nitrogen dioxide, sulphur dioxide, carbon monoxide, and ozone into a single number.

But private and international trackers such as IQAir and open-source monitoring platform AQI routinely show far higher numbers, often shooting past 600 and even crossing 1,000 on some days.

This contradiction leaves people asking the same question every year: Which numbers should they trust? And why doesn't India officially report air quality beyond 500?

India's official air-quality scale shows readings above 200 pose clear breathing discomfort to most people on prolonged exposure. Readings above 400 and up to 500 are classified as severe and affect healthy people while also seriously impacting those with existing diseases.

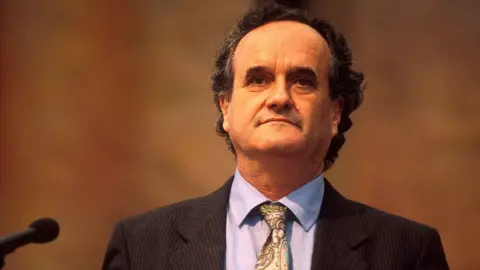

So why was that threshold introduced? It was assumed that the health impact would be the same no matter how much higher it goes because we had already hit the worst, says Gufran Beig, founder director of SAFAR. He admits that the 500 cap was originally set to avoid creating panic.

Experts suggest that international organizations do not impose such a cap, which leads to higher pollution figures on global platforms. The difference in definitions of hazardous air and monitoring instruments also contribute to the confusion.

In the end, India's AQI doesn't stop at 500 because the pollution stops there; it stops at 500 because the system was built with a ceiling.