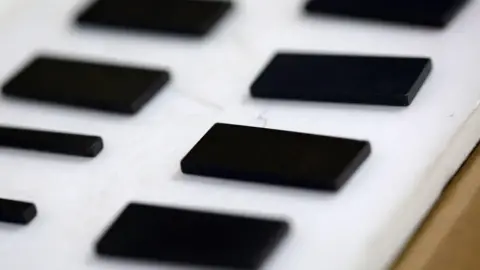

India has ordered all new smartphones to come pre-loaded with a non-removable, state-run cybersecurity app, sparking privacy concerns.

Under the order - passed last week but made public on Monday - smartphone makers have 90 days to ensure all new devices come with the government's Sanchar Saathi app.

It says this is necessary to help citizens verify the authenticity of a handset and report the suspected misuse of telecom resources.

The move - which comes in one of the world's largest phone markets, with more than 1.2 billion mobile users - has been criticised by cyber experts, who say it breaches citizens' right to privacy.

Launched in January, the Sanchar Saathi app allows users to check a device's IMEI, report lost or stolen phones and flag suspected fraud communications.

An IMEI - the International Mobile Equipment Identity - is a unique 15-digit code that identifies and authenticates a mobile device on cellular networks.

In a statement, India's Department of Telecommunications said that mobile handsets with duplicate or spoofed IMEI numbers pose serious endangerment to telecom cyber security.

India has a big second-hand mobile device market. Cases have also been observed where stolen or blacklisted devices are being re-sold, it said, adding that this makes the purchaser an abetter in crime and causes financial loss to them.

Under the new rules, the pre-installed app must be readily visible and accessible to users when they set up a device and its functionalities cannot be disabled or restricted.

All companies have been asked to give compliance reports on the order in 120 days.

The government says the move will bolster telecom cybersecurity. A Reuters report, citing official figures, says the app has helped recover more than 700,000 lost phones - including 50,000 in October alone.

But experts say the app's broad permissions raise concerns about how much data it can collect, widening the scope for surveillance.

In plain terms, this converts every smartphone sold in India into a vessel for state mandated software that the user cannot meaningfully refuse, control, or remove, advocacy group Internet Freedom Foundation said in a statement.

Technology analyst and writer Prasanto K Roy says the bigger concern is about how much access an app might eventually be allowed on the handset.

On Google's Play Store, the app says it doesn't collect or share any user data. The BBC has reached out to the department of telecommunications with questions about the app and the privacy concerns related to it.

Mr Roy adds that compliance will be difficult since the order runs counter to the policies of most handset-makers, including Apple, which historically refuses such requests from governments.

Apple has not commented publicly, but Reuters reports it does not intend to comply and will convey its concerns to Delhi. In August, Russia ordered all phones and tablets sold in the country to come pre-installed with a state-backed app, raising similar privacy and surveillance concerns.