China is facing a number of economic challenges and its government wants the next generation of consumers to start spending more for the good of all, but it is not having much luck convincing them to do so.

Officials say insufficient domestic consumption across much of society is dragging on growth, but recent graduates have more reasons than most to be cautious.

Youth unemployment has been hovering at just under 20% for some time, those who have jobs fear they could lose them, and the ongoing property crisis can make the prospect of home ownership seem unreachable, especially in big cities.

This uncertainty is encouraging many of China's youth to instead embrace frugality, and social media has been flooded with tips on how people can survive on small amounts of money.

My work is dedicated to a minimalist way of life, one full-time influencer tells the BBC.

Videos by the 24-year-old, who goes by the online name Zhang Small Grain of Rice, feature content like her using a bar of ordinary soap for all her personal cleaning requirements, rather than expensive skin cleansing products.

She can also be seen walking around shopping areas and showing off various bags and items of clothing which she says are good value because they'll last longer.

Companies pay her to feature their goods to her 97,000 followers on the Xiaohongshu site.

I hope more people will understand consumption traps so they can save. This will reduce their stress and relax them, she said.

Others focus on budget eating.

A 29-year-old using the name Little Grass Floating In Beijing posts videos of himself preparing basic dishes. He says he can have two meals for a little over $1 (76p).

I am just an ordinary person from the countryside. I have neither a good educational background nor a network of influential contacts, so I must work hard for a better life, he tells his followers.

He works for an online sales firm and claims his extremely modest lifestyle has enabled him to save more than $180,000 over 6 years.

Some have asked him online if he would expect his future wife and children to live the same way and what the end goal is. His response: I don't know.

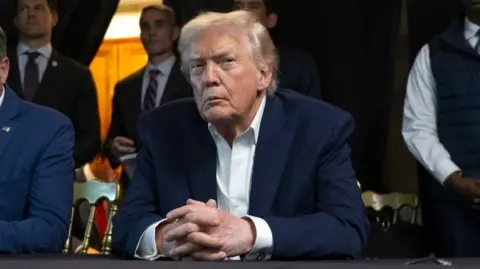

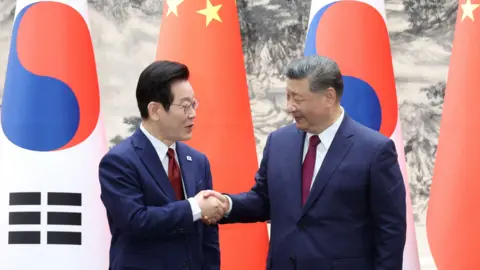

China has developed a reputation for being an unstoppable economy, able to ride out the turmoil of the pandemic and US President Donald Trump's trade war.

But analysts say it will face significant long-term challenges if it does not boost domestic spending.

While the US has a problem with people racking up credit card debt, in China it's the opposite challenge. People are already inclined to save rather than spend and this only increases when there are perceptions of tough times ahead.

The Chinese government has been promising for years to increase household consumption but it still accounts for only around 39% of gross domestic product (GDP), as opposed to about 60% in most developed countries.

Part of the problem is that today's youth are more pessimistic than in the 1990s and early 2000s.

Right now, making money is more important to me. I actually need to expand my income sources and cut my costs, a young woman in central Beijing tells the BBC.

Like many other young people, her salary has been cut, she adds.

I changed jobs, and it doesn't pay as well. Also, I don't know for how long this new job can sustain me in the future. A bad economic environment like this makes people feel down because we're not earning very much. Finding a job in the first place also isn't easy.

This level of youth unemployment - apart from spreading insecurity - makes it easier for struggling employers to cut wages because workers face a choice of accepting lower pay or diving into a highly competitive job market.

A young man, also in his 20s, says there are low-level jobs available but it's hard to find decent work in one's area of expertise.

Some of my friends are unemployed, still living at home and looking for a job, he says.

They had all kinds of majors at university from financial services to product sales. The economy is a bit off right now. I hope it gets better so we can all have a better life.

And how does he rate the chances of this happening soon? I'm not very optimistic, he admits.

A big concern for China's recent graduates is that the country is making a difficult transition from being a mass producer of cheap goods to a high-tech economy. And many of these new industries don't require as many workers.

Economist George Magnus, an associate at the China Centre at Oxford University, has been tracking this phenomenon.

He cites figures from two big recruitment firms in Beijing showing a high level of university graduates, even with master's degrees, taking jobs as delivery drivers.

It reflects the skills mismatch between the qualifications which people are leaving higher education with and what's out there in terms of demand for labour, he says.

Of course, that's not being helped by the push to become a champion in robotics and AI because, at least for the time being, this is something of a dampener on job opportunities. Tech isn't really that labour intensive.

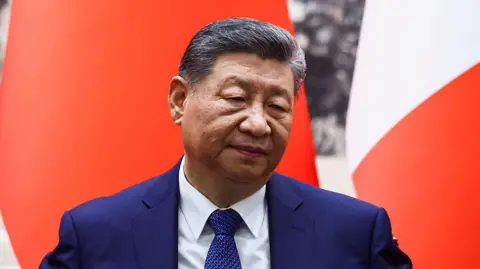

Helena Lofgren has been studying China's consumption patterns for the Swedish Institute of International Affairs and believes its economy is relying too heavily on pouring money into preferred industries and focusing on selling products overseas in a time of considerable geopolitical uncertainty.

People save more than they consume, and you need consumption to make up a bigger share of the economy than it's doing today in China, she says.

You have a very export-oriented and investment driven economy and what we see now is that these parts are too big for the economy to stay healthy.

It is all about economic imbalance. If, for example, China suddenly lost significant export revenue would it have the tools to counter this by financially empowering its enormous domestic population?

Some observers have questioned how serious the Communist Party is about increasing domestic consumption.

In recent decades, the country has thrived on an investment and export model but that approach is now facing a big challenge: deflation. Would-be customers are often waiting for the price of goods to fall.

If a young couple wanted to buy, say, a new lounge suite, it may make sense for them to wait to get a better deal.

The longer they, and many more like them, hold off from making big purchases, the more likely companies are to cut prices, leading people to wait even longer for an even better deal.

It may seem like a good idea to have cheaper goods, but deflation can force firms out of business and drag on growth overall.

This could be countered by somehow fuelling optimism amongst 20 or 30-something consumers. Building a better social safety net or increasing minimum wages might help.

There have been some attempts to do this by offering incentives to replace old cars, home appliances and other items but it has not significantly lifted consumption.

The influencer Zhang says being cautious with spending runs deep in her country's culture.

My grandfather's generation was very frugal, very thrifty. It is part of Chinese tradition. For Chinese people to be economical is in their bones, she says.