In the context of geopolitical tensions and personal loss, Tibetan refugees reflect on their longing for identity and connection to their culture while living in India.

Tibetan Exiles in India: A Search for Identity and Belonging

Tibetan Exiles in India: A Search for Identity and Belonging

As Tibetans in India navigate the complexities of exile, they confront issues of identity, statelessness, and their connection to their homeland.

The journey of living in exile has a unique emotional weight, especially for Tibetans residing in India, as they grapple with the realities of statelessness. Among them is Tenzin Tsundue, a writer and activist who recalls how teachers once told him that his status as a refugee was marked by an 'R' on his forehead. Approximately 70,000 Tibetans reside in India, having fled their homeland due to China's stronghold following the 1959 uprising.

After the Dalai Lama, their spiritual leader, led the initial mass exodus, Tibetans were welcomed in India under humanitarian grounds. However, almost six decades later, being born in India does not confer them Indian citizenship. Instead, they hold renewable registration certificates that must be updated every five years. This complicated legal status often forces individuals to choose between their current life and their identity; they can apply for Indian passports but have to abandon their Tibetan certificate, which many are reluctant to do.

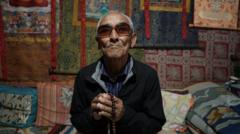

The sentiment of loss and uncertainty was palpable at the recent 90th birthday celebration of the Dalai Lama in Dharamshala, where thousands gathered despite the heaviness of exile hanging over the festivities. For many, like Dawa Sangbo—who trekked through Nepal to reach India in 1970—the longing for a home left behind remains a deep-seated pain.

Younger generations, such as Tsundue, experience this loss differently. “We are bereft of our fundamental rights—cultural, linguistic, and territorial,” he reflects. The emotional landscape includes feelings of homelessness and deprivation, complicating their ties to both India and Tibet.

Though grateful for the refuge India has provided, Tibetans lament their lack of rights—a situation that affects their economic options and personal freedoms. For those venturing to seek opportunities abroad, their identity certificate has limited recognition, posing barriers for employment and travel.

As many Tibetans look to Western countries for a future with more opportunities, personal motivations, such as family reunification, serve as driving forces. Some see leaving as a means to establish new roots and a potential path back to their homeland. However, the geopolitical friction surrounding the Dalai Lama's succession raises uncertainties among the community about the future of their movement.

Recent remarks made by the Dalai Lama proposed that a trust designated by his office would select his successor, a move China has opposed, thereby intensifying existing tensions. Many in the Tibetan community hold their breaths, balancing hope with anxiety about what change will mean after the Dalai Lama's lifetime.

While there remains an enduring hope to return to Tibet one day, the realization, as expressed by various community members, is profound: the current situation demands pragmatism amidst a complex international landscape affecting their identities, rights, and dreams for the future.

After the Dalai Lama, their spiritual leader, led the initial mass exodus, Tibetans were welcomed in India under humanitarian grounds. However, almost six decades later, being born in India does not confer them Indian citizenship. Instead, they hold renewable registration certificates that must be updated every five years. This complicated legal status often forces individuals to choose between their current life and their identity; they can apply for Indian passports but have to abandon their Tibetan certificate, which many are reluctant to do.

The sentiment of loss and uncertainty was palpable at the recent 90th birthday celebration of the Dalai Lama in Dharamshala, where thousands gathered despite the heaviness of exile hanging over the festivities. For many, like Dawa Sangbo—who trekked through Nepal to reach India in 1970—the longing for a home left behind remains a deep-seated pain.

Younger generations, such as Tsundue, experience this loss differently. “We are bereft of our fundamental rights—cultural, linguistic, and territorial,” he reflects. The emotional landscape includes feelings of homelessness and deprivation, complicating their ties to both India and Tibet.

Though grateful for the refuge India has provided, Tibetans lament their lack of rights—a situation that affects their economic options and personal freedoms. For those venturing to seek opportunities abroad, their identity certificate has limited recognition, posing barriers for employment and travel.

As many Tibetans look to Western countries for a future with more opportunities, personal motivations, such as family reunification, serve as driving forces. Some see leaving as a means to establish new roots and a potential path back to their homeland. However, the geopolitical friction surrounding the Dalai Lama's succession raises uncertainties among the community about the future of their movement.

Recent remarks made by the Dalai Lama proposed that a trust designated by his office would select his successor, a move China has opposed, thereby intensifying existing tensions. Many in the Tibetan community hold their breaths, balancing hope with anxiety about what change will mean after the Dalai Lama's lifetime.

While there remains an enduring hope to return to Tibet one day, the realization, as expressed by various community members, is profound: the current situation demands pragmatism amidst a complex international landscape affecting their identities, rights, and dreams for the future.