As Canada looks to untangle itself economically from the US, the country's landlocked oil patch is eyeing new customers in Asia through a pipeline to the Pacific. Not everyone is on board.

The oil-rich province of Alberta has had one demand for Prime Minister Mark Carney: Help us build an oil pipeline — and fast.

It's no small task — in fact, some argue it has become near-impossible to build a pipeline in Canada because of laws designed to bolster environmental protections. Three oil pipelines have died on the vine in the past decade over fierce opposition.

But Alberta Premier Danielle Smith is not deterred.

Her conservative government has taken the unusual step of drafting its own proposal for a pipeline from the Alberta oil sands to British Columbia's northern Pacific coast, aimed at reaching Asian markets. Still in the early stages, Smith hopes that by doing the groundwork a private company will eventually take over and build it.

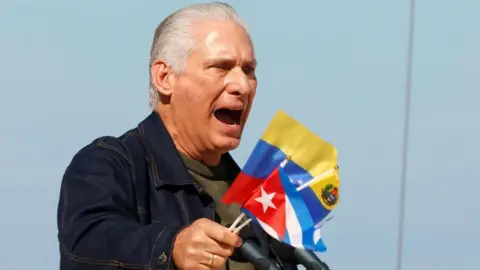

Neighbouring British Columbia, however, is firmly against it. Premier David Eby, with the left-leaning NDP, has dismissed Smith's plan as fictional and political, arguing no company wants the burden of taking it on. He also accused Smith of jeopardising his own province's ambitions to expand liquified natural gas (LNG) exports to Asia.

Smith in turn, has called him un-Canadian.

The feud between the Western provinces comes at a critical time. Canada is trying to wean itself off its economic dependence on the US amid President Donald Trump's tariffs, and Carney has signalled his desire to double non-US exports in the next decade.

That includes positioning Canada as a global energy superpower. Almost all of its energy exports, including crude oil, are currently sold to the US.

On Thursday, Carney unveiled new nation-building projects he says are key to Canada's growth. The list did not include a pipeline, but does include critical minerals mines and an LNG project in BC.

With Canada home to one of the world's largest oil reserves, Carney is now facing questions from Albertans over whether he can achieve his goals without first solving the internal rifts.

It is the perennial problem, said Heather Exner-Pirot, director of natural resources, energy and the environment at the MacDonald-Laurier Institute think tank, based in Calgary, Alberta.

It is unfortunately the main wedge issue in Canadian politics, and trust me when I say no one in Alberta wishes that their oil was the wedge issue in this country.

Asked about the divides on Thursday, Carney said the federal government and the provinces need to talk to each other.

Separately, Carney has hinted that he wants to see another pipeline built: Keystone XL to the US. Sources have told the BBC that reviving the project was raised during the prime minister's last face-to-face meeting with Trump in October, before the US president halted trade talks with Canada over an anti-tariff ad.

For Ms Exner-Pirot, the suggestion of Keystone XL may signal a resignation that the rift between BC and Alberta won't be resolved.

At the end of the day, it still looks like it's going to be easier to negotiate a new pipeline with the Americans than with British Columbia.

Carney has avoided siding with either province but has signalled his openness to a pipeline if Alberta can commit to also developing its carbon capture and storage programme.

In a statement to the BBC, Smith's office said it is working to address Premier Eby's concerns. But it said it expects Carney's government to support their project.

We have to decide if we are going to operate like a country and trade with each other, tear down internal trade barriers and stop blocking each other's projects and opportunities to trade with the rest of the world, Smith's spokesperson, Sam Blackett, said.

The BBC contacted Premier Eby's office for comment, who pointed to remarks the BC leader made to reporters on Thursday.

There is no route, there is no proponent, there is no project, he said, adding he remains frustrated that this appears to be an ongoing issue for Premier Smith.

The disagreement between BC and Alberta is part of a longstanding clash that successive federal governments have struggled to smooth over.

British Columbia is historically home to Canada's environmental movement – it's the birthplace of Greenpeace, one of the world's largest climate organisations.

Alberta's main export is crude petroleum, defending its oil and gas industry as vital to Canada's growth.

There are real grounds for a dispute, said Andrew Leach, a Canadian energy economist at the University of Alberta. The lion's share of the gains and the benefits accrue to Alberta, while the lion's share of generational risks occur in BC.

Alberta says policies including an oil tanker ban off the coast of BC are hindering energy development.

The ongoing conflict raises serious questions about Canada's ability to reconcile economic ambitions with environmental responsibilities and indigenous rights, highlighting the urgent need for dialogue and cooperation among provinces.