Rescuers and relatives searched knee-deep in water for the body of one-year-old Zara. She'd been swept away by flash floods; the bodies of her parents and three siblings had already been found days earlier.

We suddenly saw a lot of water. I climbed up to the roof and urged them to join me, Arshad, Zara's grandfather, said, showing the BBC the dirt road where they were taken from him in the village of Sambrial in northern Punjab in August.

His family tried to join him, but too late. The powerful current washed away all six of them.

Every year, monsoon season brings deadly floods in Pakistan.

This year it began in late June, and within three months, floods had killed more than 1,000 people. At least 6.9 million were affected, according to the United Nations agency for humanitarian affairs, OCHA.

The South Asian nation is struggling with the devastating consequences of climate change, despite emitting just 1% of global greenhouse gas emissions.

Monsoon floods started in the north, with global warming playing out in its most familiar form in Pakistan-administered Gilgit-Baltistan. Amid the high peaks of the Himalayas, Karakoram and Hindu Kush, there are more than 7,000 glaciers. But due to rising temperatures, they are melting.

The danger took a different form in the north-western province of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, where villagers dug through piles of rocks to rescue loved ones after a cloudburst caused flash floods.

Besides the immediate dangers, decades of mismanagement and corruption have exacerbated the situation. Illegal constructions near rivers add to the vulnerability against floods.

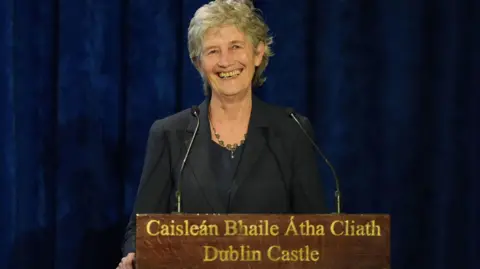

Architect Yasmeen Lari's initiatives aim to create sustainable housing solutions, one of the many attempts to adapt to the changing climate and its impacts on lives and livelihoods in Pakistan.