Shirley Chung was just a year old when she was adopted by a US family in 1966. Born in South Korea, her birthfather was a member of the American military, who returned home soon after Shirley was born. Unable to cope, her birth mother placed her in an orphanage in the South Korean capital, Seoul.

He abandoned us, is the nicest way I can put it, says Shirley, now 61.

After around a year, Shirley was adopted by a US couple, who took her back to Texas. Shirley grew up living a life similar to that of many young Americans. She went to school, got her driving license, and worked as a bartender.

I moved and breathed and got in trouble like many teenage Americans of the 80s. I'm a child of the 80s, Shirley says.

Shirley had children, got married and became a piano teacher. Life carried on for decades with no reason to doubt her American identity. But then in 2012, her world came crashing down.

She lost her Social Security card and needed a replacement. However, when she approached her local Social Security office, Shirley was told she needed to prove her status in the country. It was then she discovered she did not have US citizenship.

I had a little mental breakdown after finding out I wasn't a citizen, she says.

Shirley is not alone. Estimates of American adoptees lacking citizenship range from 18,000 to 75,000. Some may not even know they lack US citizenship.

In recent years, dozens of adoptees have been deported to their countries of birth. A man born in South Korea and adopted by an American family was deported back due to a prior criminal record — a event that tragically led to his suicide.

The reasons for this crisis are diverse, with many individuals unaware they are not citizens. Shirley blames her adoption parents for failing to finalize the correct paperwork.

I blame all the adults in my life that literally just dropped the ball and said: 'She's here in America now, she's going to be fine.'

Another adoptee from Iran shared her concerns about being classified as an immigrant, despite being raised as an American citizen. Her struggle began when she tried to acquire a passport at 38, only to find critical immigration documents were lost.

The lack of citizenship for many intercountry adoptees speaks to a larger systemic issue within the US immigration framework. The Child Citizenship Act of 2000 made some progress, granting automatic citizenship to future apprentices and those born after February 1983. However, many adoptees, like Shirley, are left without legal recognition.

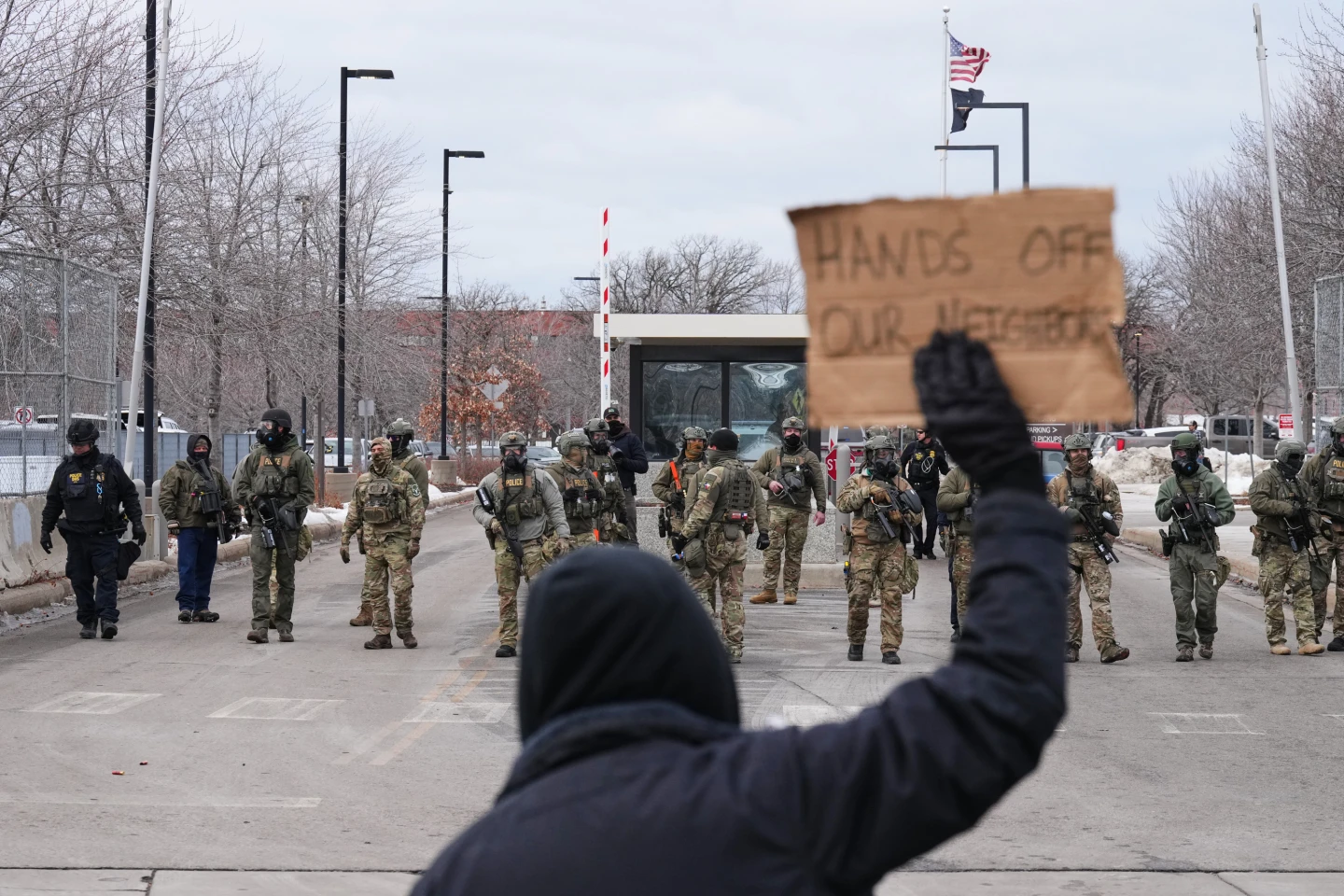

As fears of deportation increase under President Donald Trump’s administration, many adoptees find themselves seeking legal assistance. Advocates continue to press for legislative changes that would finally grant citizenship to those whose status hangs in uncertainty.

Despite the obstacles and distressing realities they face, advocates hope for unified political will to rectify the injustices these adoptees endure.