A recent study unveils that the shingles vaccine may not only prevent pain but also protect cognitive function, highlighting the vaccine's potential in public health strategies.

Shingles Vaccine Linked to Reduced Dementia Risk, New Study Reveals

Shingles Vaccine Linked to Reduced Dementia Risk, New Study Reveals

Research indicates that getting vaccinated against shingles can significantly lower dementia risk, offering fresh hope in cognitive health.

In a groundbreaking study published in the journal Nature, researchers have discovered that individuals who receive the shingles vaccine show a 20 percent reduced risk of developing dementia over a seven-year period. This finding adds to the accumulating evidence that certain viral infections may have lasting impacts on brain health and cognitive decline.

Dr. Paul Harrison, a professor of psychiatry at the University of Oxford, who did not participate in the study but has previously explored the relationship between shingles vaccines and dementia risk, emphasized the significance of this finding. He stated, "Reducing the risk of dementia by 20 percent is quite consequential from a public health perspective, especially considering the limited preventative options currently available."

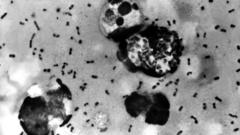

The shingles virus, which causes painful symptoms like burning and blisters, arises from the same varicella-zoster virus responsible for chickenpox. The virus can remain dormant in the body's nerve cells for years, reactivating when immune strength wanes with age. This study suggests that vaccination may not just decrease shingles outbreaks but could also play a protective role in brain health.

While the long-term effects of the vaccine beyond the seven-year mark remain under investigation, experts indicate that the shingles vaccine's potential to protect against dementia could be transformative in practice, particularly given the current lack of effective treatments and preventive solutions for dementia. As the research unfolds, the public health implications could lead to shifts in vaccination practices, underscoring the importance of shingles vaccination in older adults.

Dr. Paul Harrison, a professor of psychiatry at the University of Oxford, who did not participate in the study but has previously explored the relationship between shingles vaccines and dementia risk, emphasized the significance of this finding. He stated, "Reducing the risk of dementia by 20 percent is quite consequential from a public health perspective, especially considering the limited preventative options currently available."

The shingles virus, which causes painful symptoms like burning and blisters, arises from the same varicella-zoster virus responsible for chickenpox. The virus can remain dormant in the body's nerve cells for years, reactivating when immune strength wanes with age. This study suggests that vaccination may not just decrease shingles outbreaks but could also play a protective role in brain health.

While the long-term effects of the vaccine beyond the seven-year mark remain under investigation, experts indicate that the shingles vaccine's potential to protect against dementia could be transformative in practice, particularly given the current lack of effective treatments and preventive solutions for dementia. As the research unfolds, the public health implications could lead to shifts in vaccination practices, underscoring the importance of shingles vaccination in older adults.