When Prabowo Subianto campaigned to become Indonesia's new president, he promised dynamic economic growth and major social change. But his first year in office has not lived up to this populist platform. Rather, his ambitious pledges have been confronted by the realities of South East Asia's biggest economy.

A frustrated youth, worried about jobs, took to the streets in late August to protest against the rising cost of living, corruption and inequality - the government was forced to roll back the perks for politicians that had triggered public fury. There had been huge protests earlier in the year too, against budget cuts that hit healthcare and education spending.

What didn't help was that this coincided with an expensive free school meals programme - at an annual cost of $28bn (£20.8bn). A centrepiece of Prabowo's agenda, it aims to tackle child malnutrition, improve education outcomes and stimulate the economy. Officials describe it as an investment in Indonesia's future.

Except, in recent months images have emerged showing weak, dehydrated children - some as young as seven - hooked up to intravenous drips. They were suffering from food poisoning after eating the free lunches.

With more than 9,000 children falling ill since the scheme was rolled out in January, critics are questioning whether it's delivering at all, or straining public resources while racking up debt.

Analysts warn all of these challenges highlight broader issues in public spending and oversight - and those, in turn, point to deeper strains in Indonesia's $1.4tn economy.

It is a critical time for the vast archipelago of more than 280 million people, spread across thousands of islands. Despite steady annual growth of roughly 5% in recent years, Indonesia is feeling the pressure of slowing global demand, rising living costs and competition from regional neighbours like Vietnam and Malaysia. Both of those countries have successfully attracted foreign companies trying to diversify production away from China.

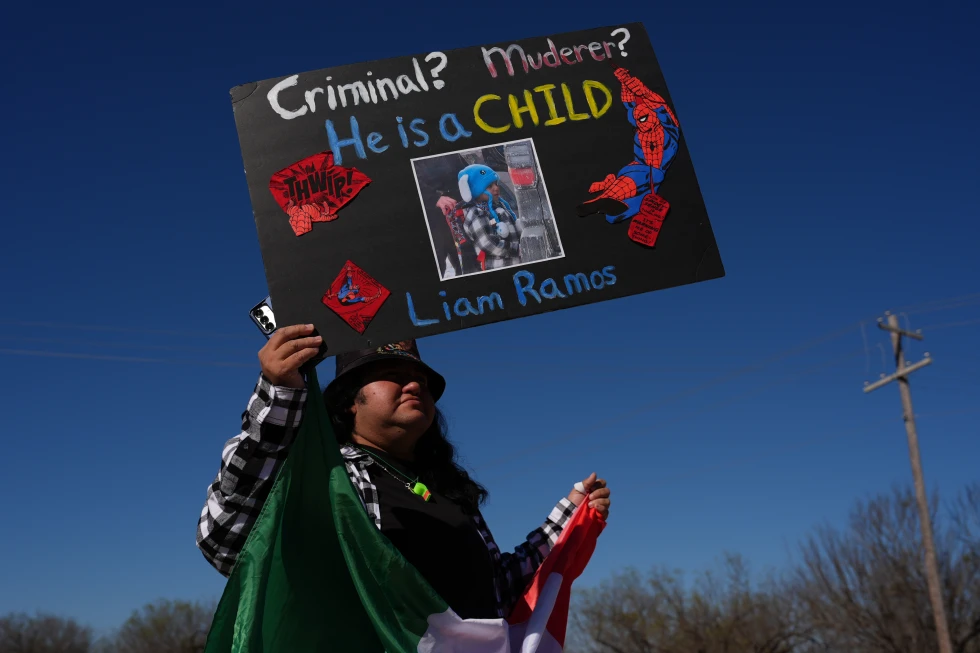

The protests in August, which left 10 people dead, captured the extent of public anger over Prabowo's government. Demonstrators accused it of prioritising prestige policies and projects over providing economic support.

Prabowo - who has set an ambitious growth target of 8% by 2029 - and his ministers continue to defend their policies, saying they will create jobs and stimulate demand.

We have an experience of growing beyond 7%. So... Indonesia knows that higher growth is achievable. But of course, we have to see the global economics and the global trade, Indonesia's Coordinating Minister for Economic Affairs Airlangga Hartarto told the BBC.

Experts say that achieving such growth will require careful management of public finances and foreign investment. A new sovereign wealth fund, Danantara, which is targeting high-impact projects across renewable energy and advanced manufacturing could spur higher growth.

Airlangga told the BBC that Indonesia is ready and willing to spend on the right sector of the economy. But ambitious and challenging commitments like the free school meals programme make some question Prabowo's priorities. Some health-focused non-governmental organisations are urging him to stop the scheme.

He defended it last month, saying Brazil needed 11 years to reach 47 million beneficiaries. We've reached 30 million in 11 months. We're quite proud of what we've achieved. Another example is India, which has the world's biggest school lunch programme, feeding nearly 120 million students.

But unlike in Brazil and India, the Indonesian programme has been accused of being ineffective, despite its much higher cost, because of the mass food poisonings. Indonesia faces unique challenges. It doesn't have the infrastructure for safe and speedy meal delivery to schools across its 6,000 inhabited islands.

US President Donald Trump's trade war has not spared Indonesia, which now faces 19% tariffs on exports to America. Indonesia - which is on the search for new markets and partners - also signed a trade deal last month with the European Union. But investment, which has spurred manufacturing and created jobs in countries like Thailand and Vietnam, has become a challenge here.

Data centres also require investment and investors are especially rattled after the abrupt sacking of the highly respected former finance minister Sri Mulyani Indrawati. Mulyani's house was ransacked in the protests by demonstrators, who blamed her for the high cost of living.

Even the current 5% rate of expansion is disputed by some economists, who also say economic data has been politicised to meet Prabowo's growth target.