The Black Hawk helicopter was ready for take off – its rotor blades slicing through the air in the deadening heat of the Colombian Amazon. We ducked low and crammed in alongside the Jungle Commandos – a police special operations unit armed by the Americans and originally trained by Britain's SAS, when it was founded in 1989.

The commandos were heavily armed. The mission was familiar. The weather was clear. But there was tension on board, kicking in with the adrenaline. When you go after any part of the drug trade in Colombia, you have to be ready for trouble.

The commandos often face resistance from criminal groups, and current and former guerrillas who have replaced the cartels of the 1970s and 80s.

We took off, flying over the district of Putumayo - close to the border with Ecuador - part of Colombia's cocaine heartland. The country provides about 70% of the world's supply.

Just ahead two other Black Hawks were leading the way.

Down below us there was dense forest and patches of bright green – the tell-tale sign of coca plant cultivation. The crop now covers an area nearly twice the size of Greater London, and four times the size of New York, according to the latest figures from the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), published in 2024.

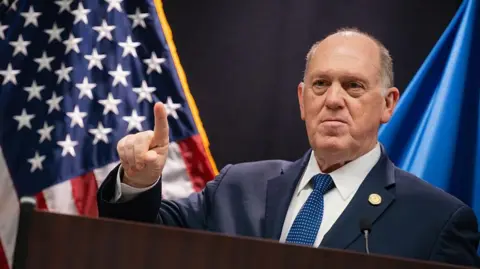

After landing, we were taken to a cocaine lab, heavily guarded and identified by its location near banana trees. Though the confrontation is always stressful, Major Cristhian Cedano Díaz emphasized the need to disrupt the cocaine production chain.

The ongoing battle is not just about the destruction of these labs but about understanding the socioeconomic forces driving local farmers like Javier to grow coca, as he struggles to provide for his family in dire conditions.

As we leave the area, Major Cedano Díaz expresses the complex and continuous effort against the drug trade, emphasizing the impact of global demand for cocaine and the ramifications it has on Colombia's environment and economy.