PORTLAND, Ore. (AP) — A gas mask dangled from Deidra Watts’s backpack as she joined dozens of others outside the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) building in Portland, just as she has many nights since July.

The protesters toe a blue line painted across the building’s driveway that reads “GOVERNMENT PROPERTY DO NOT BLOCK,” while facing off against officers who monitor from rooftops. Onlookers reported that what seem to be pepper balls rained down on demonstrators as tensions heightened. Thankfully, no injuries were reported.

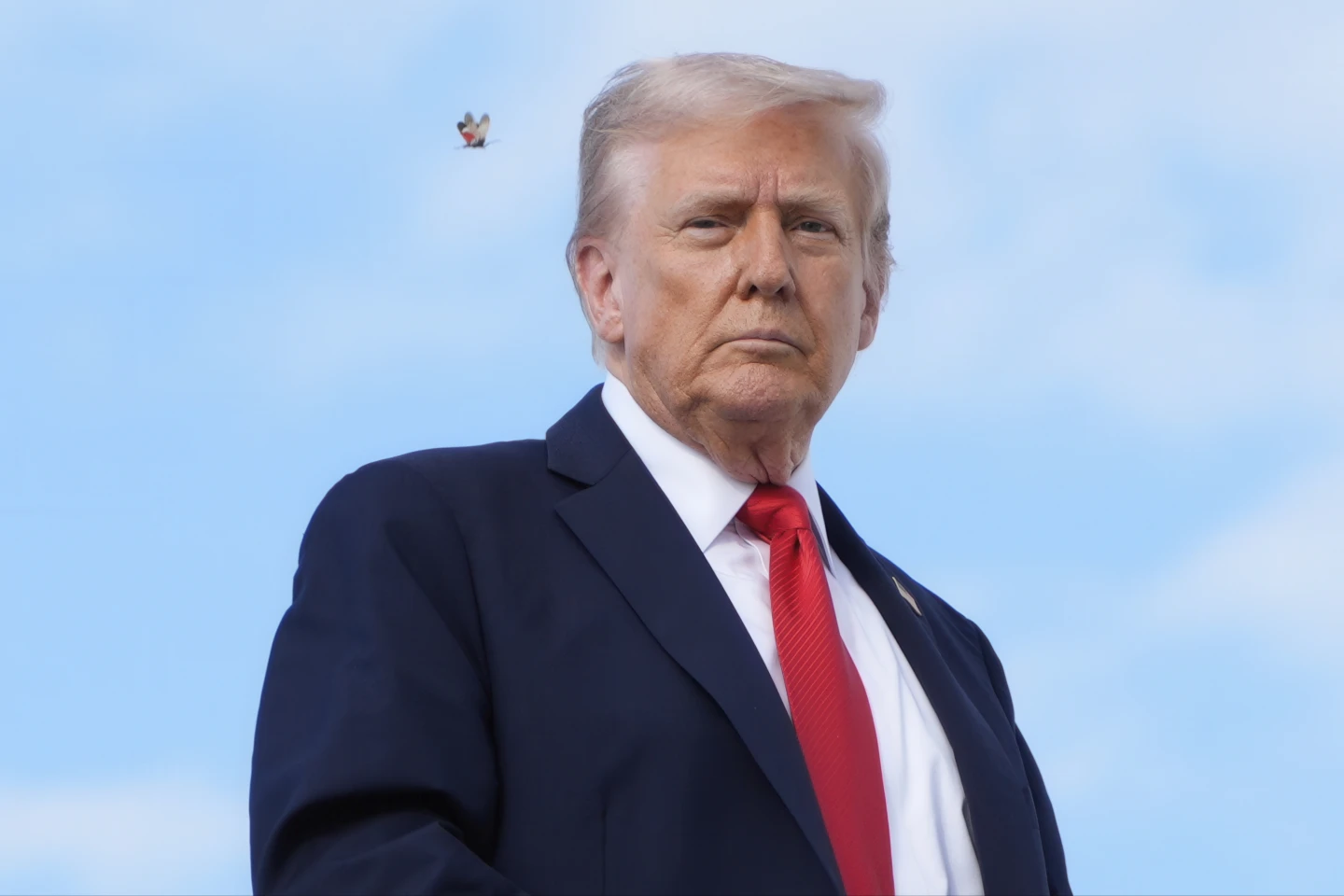

Although the protests have been disruptive, especially prompting nearby residents to relocate, they contrast sharply with the intense unrest encompassing the city after the murder of George Floyd in 2020. Still, they draw heightened attention, especially from figures like former President Donald Trump, who has referred to the situation in Portland as akin to living in hell while considering federal intervention.

Protesters have argued that silence in the face of immigration enforcement is not an option. “We have to stand up and make it known that what ICE does is unacceptable,” Watts said, labeling the agency as a “callous and cruel machine.”

Despite the ongoing protests, data shows a decline in violent crime within the city, adding an additional layer to discussions about safety and policing priorities. Residents like Casey Leger criticize the portrayal of Portland as a violent city, arguing that crime statistics do not reflect the reality of daily life.

Portland Mayor Keith Wilson has responded to Trump’s threats for federal action, stating he has not requested federal intervention and supports local freedoms while addressing violence when necessary. The juxtaposition of local opinions and state engagement continues to fuel a polarized dialogue regarding immigration, policing, and community engagement.

As long as protests continue, the ICE building will likely remain a flashpoint for the ongoing conversation about the future of immigration policy and civil liberties.