**This article explores how Donald Trump's tariffs were formulated, their intended objectives, and the potential consequences for the U.S. economy and global trade.**

**Understanding the Calculations Behind Trump's Tariffs**

**Understanding the Calculations Behind Trump's Tariffs**

**A look into the complex formula and economic implications of President Trump's trade tariffs.**

In recent developments, President Donald Trump has implemented a 10% tariff on imports from most countries, a measure that includes even higher rates for specific nations he labels "worst offenders." A crucial question arises— how exactly were these tariffs calculated? BBC Verify has investigated the methodology behind these import taxes.

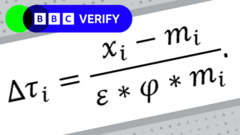

At first glance, when Trump unveiled a large cardboard chart in the White House Rose Garden, many thought the tariffs were informed by existing trade barriers and tariffs. However, the White House later released a seemingly intricate mathematical formula to explain their approach.

By breaking it down, the calculation simplifies significantly: the trade deficit the U.S. has with a country is divided by the total goods imported from that same country, and subsequently halved. A trade deficit occurs when the value of a country's imports exceeds that of its exports.

For instance, the United States has a goods deficit of $295 billion with China and imports $440 billion worth of goods from the nation. By dividing $295 billion by $440 billion, you arrive at 67%, which, when halved and rounded, results in a 34% tariff on imports from China. In the case of the European Union, the formula yields a 20% tariff rate.

Critics have raised questions regarding the supposed reciprocity of these tariffs. Reciprocal tariffs would involve an analysis of what other countries charge the U.S. Additionally, the official methodology states that these tariffs aim to abolish the U.S. goods trade deficit with each country, not reflect current foreign tariffs.

Notably, Trump’s tariffs also impact countries with which the U.S. has a trade surplus. For instance, the United Kingdom, which has a trade balance where the U.S. sells more than it buys, still faces a 10% tariff. Over 100 countries fall under this new tariff regime.

Trump's administration argues that the U.S. is losing out on fair trade deals and is impacted by foreign nations flooding American markets with inexpensive goods, undermining local jobs. He believes these tariffs will stimulate U.S. manufacturing and safeguard American employment. However, experts remain skeptical about whether this tariff strategy will meet its intended goals.

Economists have shared their insights with BBC Verify, indicating that while tariffs can diminish the trade deficit with individual countries, they are unlikely to affect the overall deficit with the rest of the world. According to Professor Jonathan Portes from King's College, the U.S.'s broader trade deficit is influenced by fundamental economic practices. Americans' tendency to spend and invest beyond their means perpetuates the situation.

Furthermore, trade deficits can stem from various valid reasons, including the efficiency of sourcing products that foreign nations can produce at a lower cost, such as agricultural goods. Thomas Sampson from the London School of Economics remarks that the underlying formula appears more constructed to justify tariff imposition against countries with which the U.S. has a deficit rather than being economically sound, sparking concern over adverse effects on the global economy.

In summary, the complexities of Trump’s tariff calculations reveal the challenging interplay between trade policies and real-world economic ramifications.

At first glance, when Trump unveiled a large cardboard chart in the White House Rose Garden, many thought the tariffs were informed by existing trade barriers and tariffs. However, the White House later released a seemingly intricate mathematical formula to explain their approach.

By breaking it down, the calculation simplifies significantly: the trade deficit the U.S. has with a country is divided by the total goods imported from that same country, and subsequently halved. A trade deficit occurs when the value of a country's imports exceeds that of its exports.

For instance, the United States has a goods deficit of $295 billion with China and imports $440 billion worth of goods from the nation. By dividing $295 billion by $440 billion, you arrive at 67%, which, when halved and rounded, results in a 34% tariff on imports from China. In the case of the European Union, the formula yields a 20% tariff rate.

Critics have raised questions regarding the supposed reciprocity of these tariffs. Reciprocal tariffs would involve an analysis of what other countries charge the U.S. Additionally, the official methodology states that these tariffs aim to abolish the U.S. goods trade deficit with each country, not reflect current foreign tariffs.

Notably, Trump’s tariffs also impact countries with which the U.S. has a trade surplus. For instance, the United Kingdom, which has a trade balance where the U.S. sells more than it buys, still faces a 10% tariff. Over 100 countries fall under this new tariff regime.

Trump's administration argues that the U.S. is losing out on fair trade deals and is impacted by foreign nations flooding American markets with inexpensive goods, undermining local jobs. He believes these tariffs will stimulate U.S. manufacturing and safeguard American employment. However, experts remain skeptical about whether this tariff strategy will meet its intended goals.

Economists have shared their insights with BBC Verify, indicating that while tariffs can diminish the trade deficit with individual countries, they are unlikely to affect the overall deficit with the rest of the world. According to Professor Jonathan Portes from King's College, the U.S.'s broader trade deficit is influenced by fundamental economic practices. Americans' tendency to spend and invest beyond their means perpetuates the situation.

Furthermore, trade deficits can stem from various valid reasons, including the efficiency of sourcing products that foreign nations can produce at a lower cost, such as agricultural goods. Thomas Sampson from the London School of Economics remarks that the underlying formula appears more constructed to justify tariff imposition against countries with which the U.S. has a deficit rather than being economically sound, sparking concern over adverse effects on the global economy.

In summary, the complexities of Trump’s tariff calculations reveal the challenging interplay between trade policies and real-world economic ramifications.