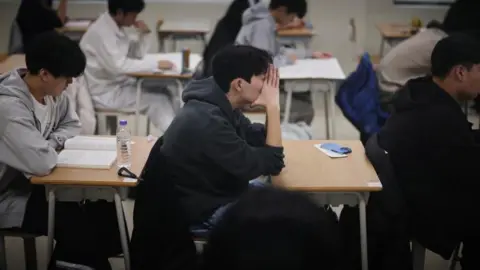

Every November, South Korea comes to a standstill for its infamous college entrance exam.

Shops are shut, flights are delayed to reduce noise, and even the rhythm of the morning commute slows down for the students.

By late afternoon, most test-takers walk out of school gates, exhaling with relief and embracing the family members waiting outside.

But not everyone finishes at that hour. Even once darkness has fully settled and night has set in, some students are still in the exam room - finishing close to 10pm.

They are the blind students, who often spend more than 12 hours taking the longest version of the Suneung.

On Thursday, more than 550,000 students across the country will sit for the Suneung - an abbreviation for College Scholastic Ability Test (CSAT) in Korean. It is the highest number of applicants in seven years.

The test not only dictates whether people will be able to go to university, but can affect their job prospects, income, where they will live and even future relationships.

Depending on their subject choices, students answer roughly 200 questions across Korean, mathematics, English, social or natural sciences, an additional foreign language, and Hanja (classical Chinese characters used in Korean).

For most students, it is an eight-hour marathon of back-to-back exams. They begin the Suneung test at 08:40 and finish around 17:40.

Blind students with severe visual impairments, however, are given 1.7 times the standard testing duration.

This means that if they take the additional foreign language section, the exam can finish as late as 21:48 - nearly 13 hours after it began.

There is no dinner break; the exam continues straight through.

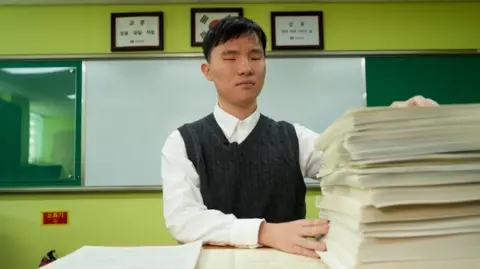

The physical bulk of the braille test papers also contributes to the length.

When every sentence, symbol and diagram is converted into braille, each test booklet becomes six to nine times thicker than the standard equivalent.

At Seoul Hanbit School for the Blind, 18-year-old Han Donghyun is among the students who will take the longest version of the Suneung this year.

Dong-hyun was born completely blind and cannot distinguish light.

With just a week left before the test, he was focused on managing his stamina and condition. Dong-hyun will take the exam using braille test papers and a screen-reading computer.

The Korean language section is particularly difficult for him.

A standard test booklet for that section is about 16 pages - but the braille version is roughly 100 pages long.

The mathematics section is no easier.

Still, he noted that things are better than they used to be. In the past, students had to do almost all calculations in their heads. But since 2016, blind test-takers have been allowed to use a braille notetaker, known as Hansone.

One of the most significant barriers, however, is the delay in receiving braille versions of the state-produced EBS preparation books - a core set of materials closely linked to the national exam.

For these students, the Suneung is not just a college entrance exam - it's proof of the years they have endured to get where they are.

Their teacher, Kang Seok-ju, said the blind students' endurance is remarkable. Reading braille means tracing raised dots with your fingertips. The constant friction can make their hands quite sore, he pointed out. But they do it for hours.

This exam is where students pour everything they've learned since the first grade into a single day. Many feel disappointed afterwards, but Mr. Kang wants them to leave knowing they did what they could. The exam is not everything.