A retrospective narrative reveals how historical changes in administration during the 20th century almost tied Dubai and other Gulf states to India, examining the implications of this connection and its erasure from modern memory.

When Dubai Nearly Became a Part of India: A Forgotten Chapter in History

When Dubai Nearly Became a Part of India: A Forgotten Chapter in History

An exploration of Dubai's potential ties to India in the midst of colonial transitions.

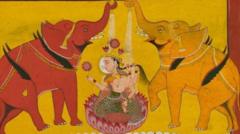

In the winter of 1956, The Times correspondent David Holden found himself on the island of Bahrain, then under British protection. His assignment included attending a garden durbar celebrating Queen Victoria's past role as Empress of India, where echoes of British India were omnipresent in the Gulf states of Dubai, Abu Dhabi, and Oman. In his observations, Holden remarked, "The Raj maintains here a slightly phantasmal sway," noting that custom and language retained strong ties to the Indian presence, with local customs incorporating Anglo-Indian traditions like Sunday curry lunches.

By the early 20th century, nearly one-third of the Arabian Peninsula was effectively administered as part of the British Indian Empire, with British officials from Delhi governing various protectorates, wielded through the Indian Political Service. The widespread Indian influence included troops and passports, extending as far as Aden in modern Yemen, which became India's westernmost port. During a visit in 1931, Mahatma Gandhi noted the emergence of young Arab nationals identifying with Indian nationalism.

Despite the significant Indian connection, this administration was shrouded in secrecy. Maps indicating the full extent of British India often omitted these Arabian territories, as public recognition could provoke geopolitical tensions with the Ottoman Empire or Saudi Arabia. However, as local political atmospheres shifted in the 1920s, Indian nationalists began envisioning their identity beyond imperial confines.

On April 1, 1937, the first partition took place, removing Aden from Indian governance, abruptly separating it from an association that had lasted nearly a century. Despite the close ties, the British authorities soon disengaged from the Gulf's governance, despite the ongoing ambiguity surrounding its administration. As the region approached independence, discussions occurred regarding whether India or Pakistan would take charge of the Persian Gulf, ultimately leading to the Gulf states' detachment on April 1, 1947.

Within months, as India and Pakistan worked to merge numerous princely states into their new nations, the Gulf emirates remained overlooked and unaccounted for. The British maintained their presence until 1971, governing the Arabian territories as part of their empire, often called the Arabian Raj. The Indian rupee remained the standard currency, while admin communications were still routed through the Indian Political Service.

Eventually, British withdrawal marked a major transition, ending more than a century of direct administration. As David Holden highlighted, this moment granted the Gulf states the opportunity for self-determination, yet they worked to reshape memory, dissolving connections to British India.

While modern narratives celebrate their independence, the Gulf states have distanced themselves from the memory of British colonial governance. This revisionist history serves to uphold the legitimacy of monarchies, obscuring the past ties to the Indian subcontinent. However, personal anecdotes reveal that buried memories persist, with some elderly locals reflecting bitterly on the shifts in societal class rooted in earlier colonial dynamics.

Today, Dubai stands as a testament to the dramatic transformation from a minor settlement to a burgeoning metropolis central to Middle Eastern affairs. Many residents remain oblivious to the historical juncture where India and Pakistan could have claimed the oil-rich territories, highlighting the profound shifts in identity and governance after the twilight of colonial rule.