At an ice rink in Vladivostok in Russia's far east, 30-year-old Dmitry Afanasyev is in training with teammates from Soyuz, the local Para ice hockey team.

The players have removed their prosthetic legs and are sitting in specially designed sleds. They're using their hockey sticks to propel themselves around the rink.

Dmitry hopes that one day he'll be a Paralympic ice hockey champion.

Making that happen won't be easy. Russian teams were banned from the last Paralympic Games over the war in Ukraine.

And like all his teammates, Dmitry was on the front line.

A mine came flying towards me, recalls Dmitry, who was mobilised to fight in Ukraine. I fell to the ground and could feel my leg burning. I looked down and everything was torn apart. I put on a tourniquet myself and told the guys to drag me out of there.

My wife's a surgeon. So, I sent her a picture of my leg and she replied: 'They'll probably saw it off.' 'OK,' I said. Whether I have one leg, or two legs. Whatever.

The port city of Vladivostok is more than 4,000 miles from Ukraine and from Russia's capital. This is Asia. Yet the consequences of a distant war in Europe are more than visible.

At a cemetery on a hill overlooking Vladivostok, there are lines of fresh graves: Russian soldiers killed in Ukraine. In addition to Orthodox Christian crosses and military banners marking each plot, stands a memorial to the heroes of the Special Military Operation, the Kremlin's term for the war.

Soldiers live forever, reads the inscription.

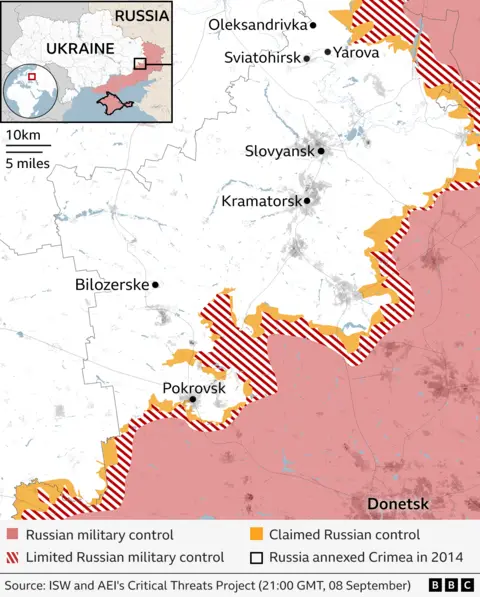

On the orders of President Putin, Russian troops poured across the border with Ukraine in February 2022.

More than three and a half years later, the war rages on.

Among the voices in Vladivostok, Svetlana expresses a desire for the conflict's end. Young musician Johnny London states that his generation often avoids discussing Ukraine, feeling it's beyond their control.

Pensioner Viktor, recognizing a visiting reporter, voices his support for Putin's policies, reflecting a divide in sentiment about the war.

The city's landscape is marked by symbols of both conflict and resilience, including a mural of Putin with a Siberian tiger, reflecting the complexity of national identity and aspirations as the region grapples with its role in the ongoing war.