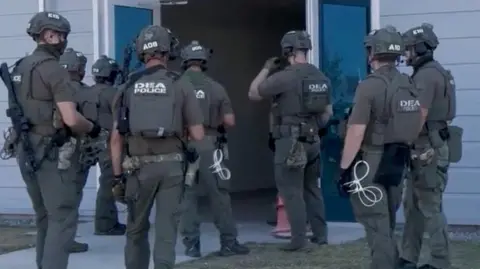

Indonesian authorities have made significant headway in unraveling an alarming baby trafficking operation that has reportedly sold over 25 infants to prospective parents in Singapore since the beginning of 2023. This week, police carried out 13 arrests across various Indonesian cities, including Pontianak and Tangerang, and successfully rescued six infants who were on the verge of being trafficked. The rescued babies are estimated to be around one year old.

The investigation revealed that the infants were kept in Pontianak, where their immigration paperwork was processed before they were shipped to Singapore. West Java police's head of general criminal investigation, Surawan, stated, “Some babies were even reserved while still in the womb.” According to police reports, the syndicate’s recruiters typically targeted expectant mothers or parents who displayed reluctance to raise their child, initially reaching out via social media before transitioning to more secure platforms such as WhatsApp.

The modus operandi included committing significant financial compensation to parents, covering delivery expenses and even preparing falsified civil documentation such as passports and family cards. Members of the group held various roles; some were responsible for locating infants while others cared for them for several months before the crucial transition to Jakarta and finally Pontianak for documentation and fabrication of identity records.

Prices for the sold infants ranged from approximately 11 million to 16 million Indonesian rupiah ($673 to $1,053). Those taken into custody, according to police, indicated the syndicate had trafficked an estimated 12 baby boys and 13 baby girls, primarily from districts in West Java. The police’s immediate goals now include identifying the adoptive parents in Singapore, utilizing travel data to track the infants' movements and the involved parties.

Surawan maintained that thus far, no cases of kidnapping have been formally recorded. Many parents consented to the sales due to economic hardship rather than abduction. However, should any agreements between parents and traffickers be confirmed, they too could face serious legal repercussions. “If it is proven there was an agreement between the parents and the perpetrators, they can be charged with child protection crimes and human trafficking offenses,” he noted.

To expand their investigation, Indonesian police have sought assistance from Interpol and their Singaporean counterparts to track down both remaining syndicate members and their customers. The intention is to find suspects and secure a broader crackdown on this disturbing network. Ai Rahmayanti, a commissioner at the Indonesian Child Protection Commission (KPAI), emphasized the emotional turmoil faced by these women, often lured through deceitful means presented as maternity clinics or shelters. She stressed the dire need to protect vulnerable women and children from falling prey to such heinous acts.

Though precise statistics on the sale of infants in Indonesia are scarce, troubling trends show a marked increase in reports related to child trafficking under the guise of illegal adoption, rising from 11 cases in 2020 to at least 59 in 2023 alone. Recent rescue operations uncovered units engaged in the sale of infants, with price tags that reflect the ongoing demand and preying on desperate circumstances, a grim reminder of the urgent work needed to combat this growing crisis in the nation.

The investigation revealed that the infants were kept in Pontianak, where their immigration paperwork was processed before they were shipped to Singapore. West Java police's head of general criminal investigation, Surawan, stated, “Some babies were even reserved while still in the womb.” According to police reports, the syndicate’s recruiters typically targeted expectant mothers or parents who displayed reluctance to raise their child, initially reaching out via social media before transitioning to more secure platforms such as WhatsApp.

The modus operandi included committing significant financial compensation to parents, covering delivery expenses and even preparing falsified civil documentation such as passports and family cards. Members of the group held various roles; some were responsible for locating infants while others cared for them for several months before the crucial transition to Jakarta and finally Pontianak for documentation and fabrication of identity records.

Prices for the sold infants ranged from approximately 11 million to 16 million Indonesian rupiah ($673 to $1,053). Those taken into custody, according to police, indicated the syndicate had trafficked an estimated 12 baby boys and 13 baby girls, primarily from districts in West Java. The police’s immediate goals now include identifying the adoptive parents in Singapore, utilizing travel data to track the infants' movements and the involved parties.

Surawan maintained that thus far, no cases of kidnapping have been formally recorded. Many parents consented to the sales due to economic hardship rather than abduction. However, should any agreements between parents and traffickers be confirmed, they too could face serious legal repercussions. “If it is proven there was an agreement between the parents and the perpetrators, they can be charged with child protection crimes and human trafficking offenses,” he noted.

To expand their investigation, Indonesian police have sought assistance from Interpol and their Singaporean counterparts to track down both remaining syndicate members and their customers. The intention is to find suspects and secure a broader crackdown on this disturbing network. Ai Rahmayanti, a commissioner at the Indonesian Child Protection Commission (KPAI), emphasized the emotional turmoil faced by these women, often lured through deceitful means presented as maternity clinics or shelters. She stressed the dire need to protect vulnerable women and children from falling prey to such heinous acts.

Though precise statistics on the sale of infants in Indonesia are scarce, troubling trends show a marked increase in reports related to child trafficking under the guise of illegal adoption, rising from 11 cases in 2020 to at least 59 in 2023 alone. Recent rescue operations uncovered units engaged in the sale of infants, with price tags that reflect the ongoing demand and preying on desperate circumstances, a grim reminder of the urgent work needed to combat this growing crisis in the nation.